Mulching 101: Why Mulch Matters

Mulch is essential to soil health because it acts as a barrier against water loss and heat, reduces weeds, improves soil structure, and provides a habitat for animals. Once you’ve found the right method for your garden or homestead, mulching is an easy way to boost your soil’s health. Plus, it’s fairly inexpensive if you collect the materials on your property. Happy mulching!

The following is an excerpt from The Healthy Vegetable Garden by Sally Morgan. It has been adapted for the web.

The Power of Mulching

Another way to keep soil covered is to use a mulch. Mulch is a layer of organic matter, compost or similar material, which is spread over the surface of the soil to act as a barrier against water loss and heat, reduce weeds, improve soil structure, provide a habitat for animals, and more. It really is essential to soil health. Most gardeners are diligent about mulching their newly planted trees and shrubs to give them a good start, but perennial beds and vegetable plots tend to get overlooked.

Mulches can be applied all year, ideally after rain so that they can trap the moisture in the soil. A good time to mulch is autumn, when crops have been harvested and you don’t want to leave the soil exposed over winter. A thick layer isn’t required, just a few centimetres will do, but don’t mulch right up to the trunks and stems of plants as this can lead to rot.

A mulch can also make it difficult for pests. Research has shown that covering bare soil with a mulch makes it difficult for flying insects, such as aphids, flea beetles and leaf hoppers, to distinguish the crop from the mulch, so it can reduce pest damage in spring while at the same time encouraging natural predators. There are lots of materials that you can use as a mulch:

- Compost A thin layer of your own garden compost is ideal, but don’t add more than a couple of centimetres in depth.

- Grass clippings These need to be spread thinly, otherwise they rot down and create a foul-smelling, rotting grassy mat. Usually, I spread fresh clippings out to dry first and then apply them to my beds.

- Leaf mould This is one of my favourite materials. Collect fallen leaves and let them rot down into leaf mould.

- Straw and hay A thick layer of straw or hay is great for trapping moisture and supplying nutrients, but it can encourage slugs, snails and spider mites.

- Mineralised wheat straw and maize biodigestate These are commercial products that you can buy to mulch your flower and vegetable beds. These materials reduce weed growth and enrich the soil, and they last for several years. They may even deter slugs and snails and, when used regularly for a number of years, gardeners have reported improved plant health and soil structure.

- Wool As a smallholder, I have a small flock of sheep and once a year, when they are sheared, I get a new supply of wool, and it’s easy to put this down to create a barrier. I think the wool (especially the really smelly daggings) deters rabbits, possibly deters slugs and snails when dry, and is also a source of nutrients. I like to use wool as a mulch around container plants and newly planted trees and shrubs, to create a thick barrier to retain moisture, and around transplanted brassicas to deter cabbage root fly. The downside is that white wool is not particularly attractive to look at.

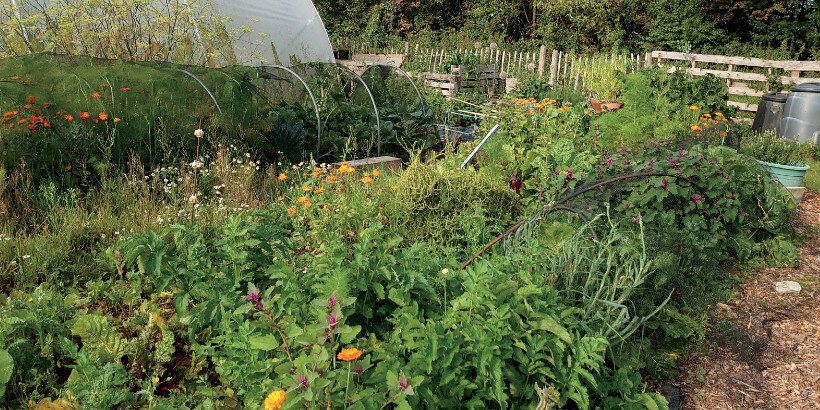

A Living Mulch

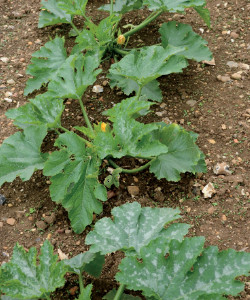

I am particularly fond of using a ‘living mulch’. As the name suggests, this is a covering of plants, sown either under the main crop or intercropped with it. I grow white clover under crops such as courgettes and brassicas. The white clover (Trifolium repens) is sown first and once this is established I plant out the main crop. The clover fixes nitrogen, helps to smother weeds and keeps the soil protected.

Its growth rate decreases as the main crop gets larger and there is more shading but, once the main crop is harvested, the clover grows on through the winter, helping to improve the soil fertility. Its flowers attract both pollinators and predators. I let the clover grow on through another year to help build up fertility. I terminate it simply by covering with cardboard.

The advantage of a living mulch is that, while the roots bind and feed the soil, the dead leaves add to organic matter without any disturbance. However, you do have to watch the relationship between the crop and the mulch. The living mulch needs to be cut back if it gets too tall and starts competing with the crop for light, water and nutrients. I have tried red clover (Trifolium incarnatum) under squash, but the plants were too competitive, so I use white clover. You can even use weeds such as ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea) or chickweed (Stellaria media) as a living mulch, while tomatoes can be undersown with coriander (Coriandrum sativum) or summer purslane (Portulaca oleracea).

Another way to use a living mulch is to intercrop by establishing strips of the clover between rows of the crop. This method works best in larger spaces, such as an allotment or smallholding, where you can grow rows of brassicas, such as Brussels sprouts, or pumpkins and squash. Establish the strips of clover, and then plant your crop in between. You may need to mow regularly to keep the living mulch from becoming too competitive. Buckwheat and annual rye can also be used in this way.

The Value of Leaf Litter for Mulching

For me, leaf litter is invaluable for boosting soil health. Not only is there plenty of it, it’s also free and easy to compost. I collect fallen leaves from paths and driveways, and either pop them in a one-tonne bag or a meshsided bin and leave them to rot down to leaf mould, which takes about a year. The resulting mould can be used as a mulch or as an ingredient in your own peat-free potting compost.

Once I have collected all the leaves I need, I sweep those lying on paths onto my flower beds. Some gardeners claim that you should clear them up. Are they right? I always look to nature and I find that soil and plants seem to cope quite well with fallen leaves. So, a few points to consider:

- Fallen leaves create a mulch that protects the soil from winter weather and suppresses weeds.

- Fallen leaves complete the cycle of nutrients, but remember that beech and oak leaves take much longer to break down than those of birch, lime, hornbeam and hazel.

- Some gardeners say that it’s important to remove fallen leaves to let the soil breathe. This is incorrect. The soil ‘breathes’ perfectly well, and the leaf litter protects the soil from the elements and stops nutrients washing out, while the leaves feed the earthworms that tunnel through the soil and improve air circulation and drainage.

- Leaf litter creates the perfect habitat for many beneficial animals, such as ground beetles and centipedes.

- If you have autumn bulbs or low-growing plants, make sure they are not buried under a thick layer of leaf litter, as it can trap too much moisture and encourage rot. Don’t let leaves pile up around trunks and stems, as they can be a source of rot. A thick layer can also make the perfect habitat for voles, which like to gnaw at wood over winter.

- You may have read advice about removing leaves from lawns. You don’t want to leave your lawn completely covered in a deep mulch of leaves, as it will kill off some of the grass, so the best method is to run a mulching mower over them so they are shredded and break down very quickly.

Should you clear up diseased leaves and burn them? This is classic advice for fungal diseases such as tar spot on acers and sycamore, but this disease doesn’t really harm the tree; it just looks unsightly. Even if you clear up the leaves under an infected tree, will you catch them all? What about the ones that have blown away? Furthermore, it seems that sweeping up these leaves barely has any effect on the level of tar spots the following year. Another disease is apple scab.

Again, the advice is to collect all the leaves and dispose of them, as the fungus overwinters on fallen leaves and in the soil, so the theory is that removing them lessens the number of spores in spring. But it’s far better to run a mower over the leaves so they are shredded and break down quickly. If you are concerned, remove the diseased leaves and compost them but, more importantly, look at why your apples are getting the disease and work on boosting soil health around the diseased trees.

No-Work, Deep Mulch

I love this variant of no-dig gardening, which I first discovered when researching no dig some 16 years ago. American gardener Ruth Stout was born in Kansas in 1884 and had a novel approach to growing vegetables. She called it ‘no-work, deep mulch’. It involved keeping a thick mulch (20cm/8in) of organic matter on her vegetable and flower beds all year round. She added more during the year to cover up any weeds that appeared and sowed and planted through the mulch, moving the mulch back to drop in the seeds before covering it again.

I’ve seen this method used successfully on an allotment, too. The allotmenteer spread a thick layer of straw over his plot and visited just a handful of times – to plant out runner beans, squash and corn, carry out checks and, finally, to harvest! Nowadays, I use a similar method on my brassica and squash beds – covering the soil with a thick mulch of hay in autumn and then planting in mid-spring. Under the thick mulch, the soil stays moist all year and I don’t have to water. To reduce the risk of slugs, I spray with beneficial nematodes before planting out and again six weeks later.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Storing seeds is the key to having a successful growing season. Follow these tips for keeping seeds organized so you’re ready to plant as soon as the time is right!

Read MoreThese hardy little berries are great to grow if you live in a colder climate. A versatile evergreen ground cover that bring both ornamental beauty and productive harvests to acidic-soil gardens.

Read MoreReady to start your silvopasture journey? First things first: which animals are right for YOUR land?

Read MoreGet ready to snuggle up with the softest wool in town! When it comes to rabbits, the Angora is the most commonly used breed for wool. It is exceptionally fine and renowned for its softness, warmth, and fluffiness!

Read MoreExtend Your Growing Season with a Cold Frame! Plant earlier in spring AND grow later into fall. Build your own cold frame and enjoy a longer harvest season! Ready to grow more, longer?

Read More