Soil to Soil: Our Environmental Impact

When you think of the impact you have on the environment, your first thought may be the waste you produce or the emissions from your car; but have you ever taken a step back and thought about the clothes you wear? A lot of the clothing produced in today’s society is just as harmful to soil and the environment as littering or burning fuel. It is important that we understand exactly what we put on our bodies, and more importantly where it came from.

The following excerpt is from Fibershed by Rebecca Burgess. It has been adapted for the web.

Nature is full of cycles. Plants and animals are born, grow, reproduce, and die, returning to the earth from which all life springs. Water travels in cycles from sea to clouds, then to land, lakes, creeks, and eventually back to the sea again. The carbon cycle moves molecules through and between ancient carbon pools on the planet, including oceans, plants, soils, and the atmosphere. One vital carbon flow in particular is the movement of carbon dioxide from the air into a plant leaf, then to roots and soil, before a portion returns to the sky. Nature cycles and recycles, returning organic material to its source—the soil—to start again. Decomposition is nature’s way of turning expired life into new life; nothing is lost, nothing pollutes, nothing is thrown away. Every part of nature has a “full accounting system” that balances income and expenditures over time even if there is an unexpected disruption, such as a forest fire or a hurricane. That’s the beauty of self-renewing cycles—they replenish nature’s checking and savings accounts.

Imagine for a moment a free-ranging airborne carbon dioxide (CO2) molecule being absorbed by the green leaf of a plant. Once there, powered by the energy of the sun, the process of photosynthesis separates the carbon molecule from the two oxygen molecules, which are subsequently released back into the air for us to breathe. The carbon is transformed into simple carbohydrates (carbon + water) including two sugars (sucrose and glucose). The plant uses carbohydrates to feed complex soil ecosystems through its roots as well as to build its very structure.

Imagine for a moment a free-ranging airborne carbon dioxide (CO2) molecule being absorbed by the green leaf of a plant. Once there, powered by the energy of the sun, the process of photosynthesis separates the carbon molecule from the two oxygen molecules, which are subsequently released back into the air for us to breathe. The carbon is transformed into simple carbohydrates (carbon + water) including two sugars (sucrose and glucose). The plant uses carbohydrates to feed complex soil ecosystems through its roots as well as to build its very structure.

Imagine the plant as one of many in a grassy meadow, which is 40 to 60 percent carbon by weight—all of it captured from the atmosphere. Now picture a hungry herbivore consuming the plants in the meadow, turning the carbon into various types of protein, including the animal’s coat—wool, for example. The wool is then shorn, processed, and dyed with natural colors, thus becoming yarn. Soon it is made into a sweater. After many years of repeated use, the sweater containing that original footloose carbon molecule ends up in a compost pile along with many other types of organic matter, gently decomposing. Eventually the finished compost finds its way to a garden, farm, or rangeland where it feeds the soil microbes that help to maintain a healthy plant community, and so begins the cycle again.

Now consider a second free-ranging airborne carbon dioxide molecule floating in the air. It is pulled into a green leaf as well, and the carbon is incorporated into sucrose, but this time the sugar molecule makes its way to the roots, where it is pushed into the soil by the plant as a part of its symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizal fungi and other soil microbes that help to produce the substance called humus. If you’re a gardener, you know all about humus: It is the dark, rich, life-promoting soil essential to growing healthy plants. If left undisturbed—not tilled or consumed by hungry microbes—the carbon stored in humus can stay safely sequestered in the soil for long periods of time. Meanwhile a vigorous “barter economy” is taking place underground between plant roots and soil microbes, exchanging carbon for essential nutrients that green plants need for thriving, which makes the plant attractive to a hungry herbivore, which consumes the leaves containing other carbon molecules, sending everything round and round once more.

The soil is one of the five great natural carbon pools, or sinks, on the planet. The other four are the oceans, the atmosphere, the lithosphere (the earth’s rocky crust), and the biosphere (where humans live). The planetary ebb and flow among these five carbon pools over short and long periods of time forms the essence of the natural carbon cycle. In modern times humans have become heavily dependent on three-hundred-million-year-old carbon trapped in the lithosphere in the form of coal, oil, and natural gas deposits to run our industry and transportation sectors. However, continuous burning of these energy sources for more than a century through engines, factories, and power plants has produced so much additional carbon dioxide that it has overwhelmed the atmospheric carbon pool, causing climate chaos. Green plants do absorb carbon being pumped into the sky, but they alone cannot balance the carbon account. Soil needs to make up the difference. Organic and eco-agricultural models of food production and land management can help achieve this goal.

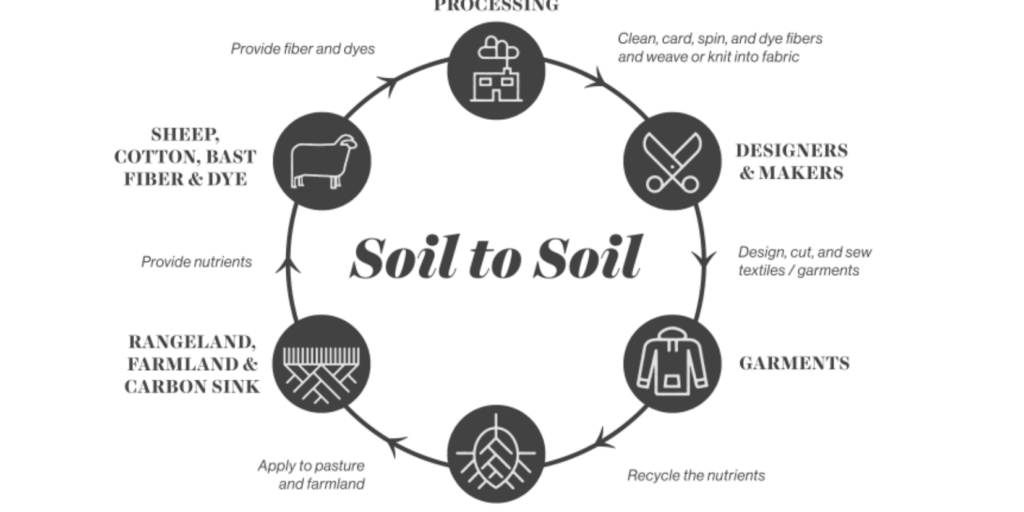

Considering Clothing from Soil to Soil

When we consider our clothing choices, we often make decisions based on color, size, and style, not on the carbon pool from which a piece of clothing originates. But the ultimate source of your clothes makes a huge difference. We should be considering clothing in the context of the following questions: Are we wearing clothing from the fossil carbon pool or are we wearing clothing grown in the soil? Are our clothes designed to return to the carbon pool from which they came? Can we compost our clothes and return them to the soil? Does our clothing degrade into smaller and smaller synthetic fossil carbon fibers (plastic) and create microfiber pollution in our oceans, soils, and landfills? How can our clothing choices help us move atmospheric carbon into the soil? Then we must discontinue our part in the production of carbon dioxide emissions by divesting heavily from fossil carbon sources of clothing: virgin acrylic, nylon, and polyester, as well as synthetic dyes and synthetic finishing agents. Once we regain our focus on natural fiber systems—materials that are farmed, ranched, and in some rare cases wild-harvested—the opportunity to restore carbon to our soils becomes a reality.

When we consider our clothing choices, we often make decisions based on color, size, and style, not on the carbon pool from which a piece of clothing originates. But the ultimate source of your clothes makes a huge difference. We should be considering clothing in the context of the following questions: Are we wearing clothing from the fossil carbon pool or are we wearing clothing grown in the soil? Are our clothes designed to return to the carbon pool from which they came? Can we compost our clothes and return them to the soil? Does our clothing degrade into smaller and smaller synthetic fossil carbon fibers (plastic) and create microfiber pollution in our oceans, soils, and landfills? How can our clothing choices help us move atmospheric carbon into the soil? Then we must discontinue our part in the production of carbon dioxide emissions by divesting heavily from fossil carbon sources of clothing: virgin acrylic, nylon, and polyester, as well as synthetic dyes and synthetic finishing agents. Once we regain our focus on natural fiber systems—materials that are farmed, ranched, and in some rare cases wild-harvested—the opportunity to restore carbon to our soils becomes a reality.

The next step is to restore and maintain healthy soils on our farms and ranches. Again, how we grow organic food is a good comparison. The same factors that make the soil productive for organic food—abundant microbial life, proper nutrient cycling, vigorous plants, holistically managed livestock, and resilient watersheds—also produce durable and self-renewing fiber for our clothes. Plant and animal fibers have historically been grown without pesticides, insecticides, or fossil fuels, and instead with natural processes that mimic natural ecology. The Soil-to- Soil system is the same whether a farmer is producing organic lettuce or organic cotton, and consumers should be just as demanding when considering the source of their clothing as they are about the source of their salads. This natural affinity between food and clothing, as well as their corresponding markets and social movements, is a critical element in the fibershed model.

Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, scientists estimate that we’ve lost 136 gigatons (136 billion metric tons) of carbon from our soils globally, and the excess carbon dioxide in our atmosphere from soil degradation and fossil carbon burning is trapping the sun’s long-wave radiation and heating our planet at a pace unprecedented in geologic history. Making matters worse, our industrial fiber and food systems are net emitters of greenhouse gases, contributing approximately 50 percent of annual global emissions. Nearly every aspect of the production and distribution of food and fiber in industrialized nations, not to mention the waste they generate, carries a large carbon footprint, including the fossil fuels required to power machinery and transportation, as well as the synthetic chemicals used as fertilizer and herbicides to keep yields up.

However, as dire as it sounds, this situation can be turned around. Soil-to-Soil systems are designed so that agriculture and its supply chains can move from being net emitters of greenhouse gases to net reducers. In other words, by employing region-appropriate carbon farming practices, food and fiber systems can help build up the soil carbon pool over time and thus become part of the solution to climate change. This turnaround in food and fiber systems is good for farmers and ranchers as well, because global warming is creating increasingly frequent and unpredictable weather extremes, making it more difficult to farm and ranch across a wide variety of landscapes. We are seeing an increase in soil moisture loss due to evaporation and an increasing rate of soil erosion due to severe weather events, from floods to droughts. The overall heating of our planet is also contributing to carbon losses in our soils. Altogether, these outcomes of climate change are leading to wide- spread soil degradation. There is a great need to create resiliency strategies that can support farmers and ranchers in growing and producing our fiber and food regeneratively.

However, as dire as it sounds, this situation can be turned around. Soil-to-Soil systems are designed so that agriculture and its supply chains can move from being net emitters of greenhouse gases to net reducers. In other words, by employing region-appropriate carbon farming practices, food and fiber systems can help build up the soil carbon pool over time and thus become part of the solution to climate change. This turnaround in food and fiber systems is good for farmers and ranchers as well, because global warming is creating increasingly frequent and unpredictable weather extremes, making it more difficult to farm and ranch across a wide variety of landscapes. We are seeing an increase in soil moisture loss due to evaporation and an increasing rate of soil erosion due to severe weather events, from floods to droughts. The overall heating of our planet is also contributing to carbon losses in our soils. Altogether, these outcomes of climate change are leading to wide- spread soil degradation. There is a great need to create resiliency strategies that can support farmers and ranchers in growing and producing our fiber and food regeneratively.

Building soil organic matter has an important additional benefit: It increases the soil’s water-holding capacity, thus reducing agriculture’s need to draw from aquifers and surface water sources. This means water can be conserved for other uses, including the survival of imperiled species, lessening the tension between biological diversity and human-managed systems. From an economic perspective, improving the soil’s ability to capture and retain water can be done naturally and relatively inexpensively while increasing yields and net primary productivity on working lands. This equates to increased fiber and food security and less land required to meet our essential needs.

Focusing on the ground beneath our feet is a place-based strategy that every community can engage in without the need for complex technologies that come with hidden costs.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Embracing the tradition of saving seeds is a powerful practice for both home gardeners and seasoned horticulturists alike.

Read MoreThe Netherlands is ranked second in agricultural export volume behind the United States. Their secret weapon? Greenhouses and hoophouses.

Read MoreGet ready for a bountiful harvest! Storing seeds is the key to having a successful growing season. Follow these tips to keep your seeds organized and ready to plant 🌿🪴 Get ready to plant like a pro this season!

Read MoreThese hardy little berries are great to grow if you live in a colder climate. A versatile evergreen ground cover that bring both ornamental beauty and productive harvests to acidic-soil gardens.

Read MoreGet ready to snuggle up with the softest wool in town! When it comes to rabbits, the Angora is the most commonly used breed for wool. It is exceptionally fine and renowned for its softness, warmth, and fluffiness!

Read More