How to Brew Mead at Home: Ginger-Apricot Mead Recipe

When Jereme was in North Carolina for the 2016 Mother Earth News Fair in Asheville, he picked up a local honey made from summer wildflowers. Why? He was inspired after visiting Fox Hill and sampling their Special Reserve Mead, which has hints of ginger and a unique blend of buckwheat honey and some lighter varietals.

He started a one-gallon batch of mead with dried apricot and ginger. Jereme said the mead performed admirably in taste tests, even after passing the “sweet spot” most meads reach (meaning they taste lovely while “young” and sweet but reach a point where most of the sweetness has fermented away and they need time to age out harsh flavors).

The following is an excerpt from Make Mead Like a Viking by Jereme Zimmerman. It has been adapted for the web.

Honey for Mead Making

The sheer number of honey varieties, combined with regional and seasonal availability, can make it difficult to choose a specific type of honey for each batch of mead. Generally, when selecting honey for mead making, use the following criteria (in order of importance):

- Quality

- Raw, unfiltered, and unpasteurized

- Locally produced

- Varietal

- Price

- Convenience

You may have to switch the order around, but always consider the first two before even thinking about the rest.

If honey providers say their honey is local and raw (and are being honest about it), then you can be assured it is high quality and thus appropriate for mead. Honey you buy in the average grocery store, particularly if it says it is “blended,” is very likely faux honey. It will produce mead that is plenty drinkable because it has fermentable sugars and tastes like honey, but is often of dubious origin. Anyone who has looked into buying a gallon of honey to use for mead knows that honey is not a cheap product. Because of this, some companies in China and their American distributors have taken advantage of loopholes in the FDA’s definition of honey to produce a product resembling honey that is better suited to the wallet of the average American consumer.

If honey providers say their honey is local and raw (and are being honest about it), then you can be assured it is high quality and thus appropriate for mead. Honey you buy in the average grocery store, particularly if it says it is “blended,” is very likely faux honey. It will produce mead that is plenty drinkable because it has fermentable sugars and tastes like honey, but is often of dubious origin. Anyone who has looked into buying a gallon of honey to use for mead knows that honey is not a cheap product. Because of this, some companies in China and their American distributors have taken advantage of loopholes in the FDA’s definition of honey to produce a product resembling honey that is better suited to the wallet of the average American consumer.

This “honey” is very transparent and clear and won’t crystallize like real honey, as it has been filtered and all traces of pollen removed. To enable production of large amounts at low prices, it is then mixed with additives like high-fructose corn syrup and sugar-water. Often it also contains traces of pesticides, antibiotics, and other unpleasant substances.

Many legitimate beekeeping companies have taken to using the TRUE SOURCE HONEY label to pledge that their honey is all-natural. True Source Honey is an initiative started by US honey producers to prevent honey from being devalued due to unethical foreign sourcing. Members place the TRUE SOURCE HONEY label on their honey jars to show that they are committed to producing real honey. More than anything, what this tells us is that the best policy is to get to know your local beekeepers, so that you can always be sure you’re using local, trustworthy honey.

But what if you want to make several batches of mead, or plan on making mead during the slow season for honey (autumn through late spring)? Often you can still find local honey during the off season, but price and convenience do play a factor unless you’re blessed with lots of time and money to hunt down the highest-quality honey regardless of price. I’ll admit, price and convenience are often the determining factors when I purchase my honey for mead, but with some caveats. Since I’m fortunate to have stores near my house that regularly stock local honey at reasonable prices, these stores are where much of the honey for my mead comes from. I know it’s local, I trust its quality, and I’m not breaking the bank. But for the same reasons, I’m usually limited to sourwood and various wildflower honeys. This is not a bad thing at all, as these are great honeys for mead. When I travel, I like to look for varieties of locally produced honey that I’m not able to get at home.

Ginger-Apricot Mead

Prepare a yeast starter through wild fermentation.

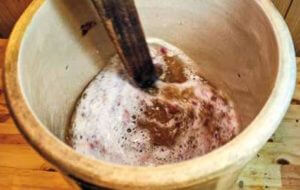

To aerate mead must when open-fermenting, stir vigorously with a stir stick to create a vortex, reverse direction, and repeat for at least five minutes. This is particularly important for wild ferments.

For a semi-sweet mead, blend approximately one quart (2.3 pounds) of honey and one gallon of slightly warmed spring water.

Add three to four dried apricots or as many fresh, whole apricots as you’d like.

Thinly slice a chunk of fresh ginger and drop in 3-4 slices (about 1 in. in length each).

Add 5-6 organic raisins.

Ferment in an open-mouthed container covered with a dish towel or cheesecloth for 1-2 weeks, stirring 2-3 times daily.

Rack (transfer) to a narrow-necked jug with an airlock or balloon over the opening.

Rack off lees (yeasty sediment on the bottom) after about a month and 1-2 times every couple of months thereafter. It should be ready for bottling or even drinking within 4-6 months. I highly recommend bottling and aging at least a few bottles.

At any point in the process, if you taste and the apricot or ginger doesn’t stand out enough for you, add more and continue to taste test until it has reached a level you like. Keep in mind that some flavor subtleties won’t come out until the mead has aged in a bottle for six months or more.

Don’t forget to toast to your friends with a hearty “skal!”

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Elevate your evenings with this delightful non-alcoholic mocktail syrup. Whether you’re looking to relax before bed or want something new to add to your tea, this non-alcoholic herbal nightcap mocktail will do the trick.

Read MoreSearching for a new way to utilize seasonings? Look no further than mint salt! This game-changer is bound to mix up the way you season meals in the future.

Read MoreFire Cider is great for stimulating digestion and warming you up from the inside out, no matter the season. This beverage can be prepared in water or tea as desired.

Read MoreReady to shake up your fermentation game? Try making Kvass, the ultimate beginner-friendly recipe! This nourishing beverage calls for just a few simple ingredients and only takes a couple of days to ferment. It’s easy, delicious & perfect for beginners.

Read MoreStart your journey to making homemade ghee! Discover how to make this delicious staple and incorporate it into delicious recipes — like our Citrus-Glazed Chicken recipe. Get ready to level up your cooking game with homemade ghee!

Read More