A Community Food Forest: Planning and Managing

As Benjamin Franklin stated, “By failing to prepare, you’re preparing to fail.” A good community food forest will always require robust planning but don’t let that scare you!

By breaking down the work into the following five project management phases, you not only establish an initial plan you’ve also developed a dynamic system to allow for adjustments throughout the project.

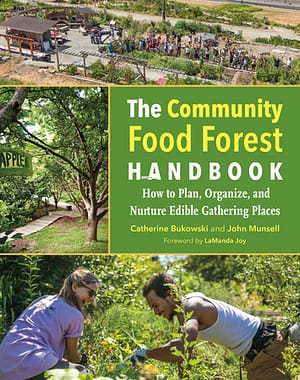

The following excerpt is from The Community Food Forest Handbook by Catherine Bukowski and John Munsell. It has been adapted for the web.

Project Management Phases

Our experience studying and leading community food forests taught us that starting with the basics and seeking to understand fundamental management phases leads to effective planning. This is true whether the food forest is an independent project or part of a larger community initiative.

Thinking about phases helps leaders identify and plan for when, where, and how to direct precious resources instead of trying to do everything at once. We will provide a general overview of the following five main phases associated with project management and relate them to community food forests:

- Initiation

- Planning

- Establishment

- Monitoring and maintenance

- Closure

The phases are listed in the order they occur when applied to projects that have a linear timeline. However, we found that these phases often did not occur in a linear fashion for community food forest projects.

For example, one section of a site might be in the establishment phase, while another previously established section is in the monitoring and maintenance phase, while yet another area is being planned for a future planting.

These phases do not only apply to the installation of plants, either.

Volunteer education could be in the planning process while another is currently being implemented. At the same time, the steps to close down and document a recent workshop might be taking place while future visioning is happening for the next.

Soliciting feedback from participants and deciding whether or not to offer the same or a similar workshop in the future is part of closure. The information gathered provides direction for planning the next volunteer education phase.

Initiation

Initiation is the origination and early evolution of an idea.

It starts when the idea is born and gets underway when the thought is shared with others to test the potential. With positive feedback, excitement begins to build.

This is typically the phase when people reach out to those they know could be interested in the idea to gain support and encouragement.

This is an exhilarating time for a community food forest project.

Brainstorming is a great and exciting way to generate ideas and start working on details such as what species will be desirable.

It is tempting to start on a detailed food forest design, but typically a full design is a product of the planning phase due to the importance of first acquiring land and seeking community input.

While visiting food forests across the country, it became evident that it is next to impossible to predict how many people may be involved when initiating a community food forest. There may be scores of people involved or just a handful and it is best to prepare for both.

Identifying your initial objectives is helpful to avoid a sense of being immediately overwhelmed by the overall scope of what needs to be accomplished. Let us break down some of the initial steps of initiation and consider how they relate to community food forests.

Property.

One of the first details to consider is space. Is property easily available? If not, what will it take to locate an appropriate place and negotiate a lease or tenure? At this stage, it may be helpful to seek advice from professionals such as those mentioned in chapter 9.

For example, an urban forester could specify green spaces where increasing canopy coverage is possible, or an urban planner may know of suitable land where future development is unlikely.

The owner of a vacant lot may be able to be contacted by checking a city’s vacant property registry. Finding the best location and securing permission can be a lengthy process.

It is best to start early as the space selected will influence the participants involved, the planning process, and dynamics with the broader community.

Community context.

Initiation is also the ideal phase in which to think about historical and contemporary issues in a community and the role a food forest can play in adequately and fairly addressing both.

Is there a historical context that will provide cultural meaning to the design? Is there a history of neighborhood division to be bridged through careful planning? Or is there strong unity in a neighborhood that will support the project and make selecting a location easy?

These types of questions are critical to early success; in chapter 11, we offer more of these important questions and discuss why they are important.

Another detail to reflect on early is whether enough people have the time, energy, and interest to pursue a community food forest and take it to the planning phase.

Mission and target audience.

While brainstorming about your community food forest, an important early step is to ask yourself this question: Why this project instead of another?

Critical reflection (discussed in chapter 8) is helpful for this type of discussion. There are multiple ways to increase food security in a town, build community, or act on behalf of social justice.

Because of this, it is worthwhile to explore questions such as: Who will the community food forest serve? Why is a community food forest the most appropriate solution for the people it will serve?

Systems thinking, community capitals, and critical reflection are helpful in these brainstorming sessions. After identifying why a community food forest is the most appropriate project, leaders can go on to identify the scope.

Scope.

Scope sets limits around what the project can and cannot address. It focuses a project by recognizing it cannot be the solution to every problem.

Important when defining scope is to revisit project vision and objectives. The vision will go through multiple stages of development and the first iteration is one that gains peer approval to pursue.

During the pursuit, there is a need for collecting feedback and opinions from others about the vision. Future iterations should then be collectively developed and shared so that everyone sees their part reflected and is willing to work together toward making the vision a reality.

Setting the scope of a project also makes it easier to identify who should be involved and define their roles and responsibilities. We have included a set of archetypal roles for your reference in “The Core Group,” on page 174; this positional lineup is a helpful starting point and can be used to think about who can fill critical roles from the outset.

Once you have a better idea of who will be involved, you and fellow leaders can form an organizational structure or decide on a decision-making process. Because decision making often needs to begin almost from project inception, it is better to agree upon a decision-making system well before the planning phase.

Feasibility.

Lastly, as part of feasibility discussions, leaders need to consider risks, assumptions about a project’s aims, and other issues that potentially will affect the community food forest. Being realistic about these components allows the group to plan for how to avoid or deal with them if encountered during the project.

For example, with any community food forest, there is a risk that the organization or group of people who initiate the project will either dissipate or move on. In chapter 7, we describe how this happened at the Dr. George Washington Carver Edible Park in Asheville when the founders of the organization moved from the area.

Because Asheville agreed to share responsibility early in the process, the park was able to weather the transition to a new caretaker organization under the oversight of the municipality. This is an example of how site continuity can be preserved through planning with a public partner who agrees to share some of the risk.

Planning

Sometimes it is difficult to determine when initiation stops and planning begins. Usually, there is a transition period when they are blended. Initiation might need to occur in a couple of months or it might take several years until all necessary approvals are in place and in-depth planning can begin.

During this time, planning on specific aspects may be underway. The planning phase grounds the details developed during the brainstorming and stakeholder analysis in the initiation phase.

Defining project schedules, agreements, and communication strategies is part of planning.

Leaders will work with other stakeholders to develop a realistic timeline of events and dates for resources, equipment, material, labor, and other necessities.

In certain regions, the timing for acquiring plant material, transplanting, or direct seeding is determined by climate, which makes it easy to develop a timeline. On-the-ground food forest layout and plant establishment generally need to occur in phases spanning several growing seasons.

Planning sets up the next phase of action and community food forest establishment.

In chapter 8 we discuss agroecological concepts that provide useful guidance on ideas, design principles, and practices to incorporate into a plan. We present the story of the Wetherby Food Forest, in Iowa City, which demonstrates the importance of starting small and expanding over time as a site proves sustainable.

Planning also includes thinking ahead about how to fill gaps in planted areas that may occur due to plant mortality. Keeping future needs in mind such as filling in gaps helps plan for managing things such as when and how much funding to set aside or how and when to organize a community drive to accept plant or money donations.

In addition to site design, it is important to plan for how the site will effect change or serve a community population.

During the initiation phase, the relevance and purpose of your community food forest is determined. Developing a thorough strategy for how that change will take place through initiatives tied to the community food forest is central to the planning phase.

To help develop this strategy, we present the theory of change and ways to measure whether the project is effective in the next chapter.

Financial planning is critical and may require thinking a year or more in advance.

For example, it is important to plan ahead regarding deadlines related to grant cycles and timing requests to municipal allies in order to meet the requirements of governmental fiscal calendars.

Sources of funding also help determine what constitutes success along with metrics on how to measure progress toward it. Stakeholders often have different criteria for success.

Being realistic about what is possible with the funding available and working out an agreement on what an acceptable level of success is for specific criteria will help everyone land on the same page about project expectations.

A communication plan often includes multiple levels.

The core team will need to decide on methods of communication among themselves and also how the team will engage with the public or others.

For example, the Mesa Harmony Garden in Santa Barbara, California, sends weekly emails to their listserv to update everyone on work that needs to be done, important events, and general news about what is happening at the garden or what is ready for harvest.

Other sites, like Beacon Food Forest in Seattle, use social media sites to post information, events, and photos to entice continued engagement.

Establishment

Overall, this is an action-oriented phase when plans are put into motion. Following through on a communication plan is one of the biggest tasks in this phase.

Within the core group, communication should be constant.

Updates on progress, setbacks, and general feedback needs to occur regularly.

Communication with volunteers outside of the core group is also critical in this phase because volunteers are most often the labor and energy source that take community food forests from a design to an established physical project.

Monitoring is largely represented in the next phase, but it begins during establishment to assure quality of work and project status and, even more important, to celebrate achievements!

Feedback loops begin during this phase as information is collected on what works and what does not.

Checkpoints should be scheduled often, in order to pause, assess, and then inform project partners and funders of how the project is unfolding vis-à-vis the plan. Everyone involved in a project or program has expectations for progress, so managing to keep them realistic and agreeable is crucial.

This is particularly the case during establishment, which transforms your community food forest concept into reality.

Monitoring and Maintenance

Monitoring and maintenance entails ongoing upkeep of a community food forest and periodic evaluation of its progress. The work of monitoring the social system can be even more important than maintaining the plantings.

Expect an ongoing need to monitor how volunteer workdays are scheduled, who will lead them, and whether volunteers need training in pruning, coppicing, weeding, or other techniques.

Learning more about volunteers and assessing needs can help stakeholders decide whether or not workshops in gardening, design, construction, vegetation maintenance, and so on are needed.

If maintenance goals are not being met, adaptation becomes necessary.

In terms of physical maintenance of the site, protocol should be in place for how underperforming, dead, or dying plants will be replaced or rehabilitated and new plants added.

It is also a good idea to set guidelines for maintenance and monitoring of infrastructure such as trails, benches, signs, and picnic tables.

Closure

Closure in a community food forest project can signify success, such as a desired level of community participation or a particular volume of fruiting.

Closure can also be the end of a particular phase of the project, such as initial installation, or a predetermined point in time where project goals are revisited.

We noted during our research that the idea of closure did not reflect the goal for community food forests to have long-term viability.

This made discussing closure or pinpointing when it was happening confusing and difficult. It was easier to recognize times of closure in relation to discussions beginning about future visions for the next phases of growth, which is reflected throughout the case study chapters.

Documenting the project can be of great value during closure and other phases.

It is helpful to decide in advance what archival procedures you will follow to record accomplishments and provide summaries of lessons learned.

For example, the development of the Dr. George Washington Carver Edible Park was chronicled in a series of newsletters, which turned out to be very helpful because they created a public archive.

Community members must also decide on mechanisms for measuring expectations and satisfaction as a way to make real-time project improvements.

Closure at certain junctures may only be fleeting.

The whole community involved with a food forest, not just the project leaders, must be ready and willing to adapt to unexpected events such as volunteer vacancies, new policies, and natural disturbances like windstorms or human damage from vandals or plain wear and tear.

Instead of planning for turnover or the unpredictable as project leaders do, closure, whenever it may occur, reflects the frame of mind among all involved that succession and change is natural in a social system and adaptation is a wise policy.

Recent Articles

Beavers are ecological and hydrological Swiss Army knives. Capable of tackling just about any landscape-scale problem you might confront.

Read MoreWhen you’re walking around the grocery store looking at the vegetables, it’s probably hard to imagine that a century ago there was twice the amount of options.

Read MoreIf you love tomatoes, you probably already know just how many varieties of these summertime staples there are. But do you know what makes each one unique?

Read MoreAdding the long game of trees to your system results in a deeper and more reliable, resilient and profound presence to your annual vegetable production.

Read MoreFor people who enjoy foraging for food in the wild, there are plenty of mushrooms to choose from — “ten thousand mushroom species to be considered on the North American continent alone”. But foraging for mushrooms should never be thought of as a game of chance. You need to know all the clues when it comes to identifying…

Read More