The Seven Layers of A Forest Garden

When you create a forest garden, you give nature the reigns and let it take the hard part off your hands. All you need to do is get to work on creating the seven layers, and the forest will take care of the rest.

The following is an excerpt from The Home-Scale Forest Garden by Dani Baker. It has been adapted for the web.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs by Dani Baker.

Layers of A Forest Garden: Letting Nature Do the Work

Bill Mollison, the originator of the term permaculture, defines the word in his classic text Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual. He writes, “Permaculture (permanent agriculture) is the conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystems which have the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems.”

Principles of Permaculture

Because the principles of permaculture are derived from nature, the end result is resilient and regenerative, just as a forest, meadow, or other natural ecosystem is. Permaculture principles have a wide range of applications well beyond an edible forest setting. In fact, permaculturists rely on the basic principles to guide many kinds of decisions— from where they choose to build a toolshed or create a pathway to what types of heating system they install in their house.

The concepts of permaculture originated in Australia, but now there are farmers, homesteaders, and homeowners all over the world who are applying its very practical ideas. Although I don’t consider myself a permaculturist, I continue to learn about its principles and applications by reading books, attending workshops, and experimentally applying them in my own garden.

Maximizing diversity is desirable at all levels. Here a diverse ground cover in spring includes strawberries, wild blue lupine, perennial blue flax, and coneflower.

Maximizing Diversity in Your Forest Garden

In nature, there are few monocultures. Most natural landscapes feature a wide variety of plants, and this diversity offers many benefits. It creates niches where beneficial insects such as ladybugs and dragonflies and animals such as birds and toads can make their homes and find sustenance.

In the face of unfavorable weather, biodiversity ensures that some species will likely survive or even thrive under the challenging circumstances. Likewise, as the climate continues to change due to global warming, a diverse flora will more likely include some species that can adapt effectively to the changes.

Ensuring Plant Health & Resilience

A varied planting makes it harder for pests or diseases to find their object. A monoculture, such as an orchard planted exclusively with apple trees, is like an open invitation to insects to enjoy a sumptuous buffet of their favorite food or to disease organisms to spread unfettered.

In contrast, a lone apple tree surrounded by a variety of other trees as well as shrubs, flowers, and ground covers presents many obstacles and distractions to apple pests, making it difficult for them to find and lay eggs on young apple fruits. Disease may spread more slowly and be less devastating. In sum, landscape diversity ensures health and resilience.

Strategies for Maximizing Diversity

I’ve implemented the principle of maximizing diversity in my garden in several ways, including alternating species, planting mixed hedges and ground covers, and designing to maximize the edge effect.

I alternate species throughout my garden. As much as possible, I avoid placing two plants of a particular species side by side. For example, in a bed containing fruit trees, I included an apple, a cherry, a mulberry, a peach, and a persimmon, all surrounded by an array of other kinds of plants. There are exceptions to this rule. I do plant berry bushes such as honeyberries in a group for ease of U-pick harvesting.

Making Use of Monocultures

In the United States, most traditional hedges or windbreaks are monocultures, such as a rose hedge or a cedar windbreak. Ground cover plantings tend to be single species, too—a big swath of pachysandra or periwinkle, for example. Whenever I design a hedge or windbreak, though, I make it as varied as possible.

I modeled my hedges in the Enchanted Edible Forest after the ancient hedgerows I observed in the rural parts of England where, I was told, you could guess the relative age of a hedgerow by the extent of diversity found in it. Over the long span of years, birds nesting in the dense greenery of a hedge excrete viable seeds of a wide range of plants. Some of those seeds germinate.

It’s one of nature’s best planting methods, and it effectively increases a hedge’s diversity over time. The hedgerows in England contain tall trees, bushes, brambles, and many other species. Following that model, I designed my hedges and windbreaks to include a diversity of trees, bushes, brambles, and ground covers. Whenever I want to add a tree to my garden but can’t find a spot for it, my go-to solution is to plant it in a hedge.

Forest Garden Ground Covers

A wide, grassy path allows early-morning light to bathe all the branches of the cherry trees on the right.

In some situations, a uniform ground cover is inevitable because one species is so dominant it displaces others in the area, or because only one type of plant is suited to a challenging habitat. But apart from such circumstances, diversity is also desirable in a planting of ground covers. In most locations, having two or more ground covers interplanted or bunched in groups by species contributes to the overall diversity of the garden.

The overall goal in designing a forest garden is to follow nature’s model. In nature the greatest diversity is often found at an edge where two habitats meet, such as where a meadow transitions into the woods. A riverbank or lakeshore is also a natural edge. In an edible forest garden, the intent is to mimic the diversity of plants found in a forest edge, possibly the most diverse habitat of all in a temperate climate.

Where Should The Forest Garden Begin?

At the edge of a natural wood-land, there is abundant light, which encourages plant growth in many layers, from the treetops all the way down to the ground surface. This is quite different from the environment farther into the woods, where very little sun reaches the ground level and only shade-loving plants can survive. It’s possible to plan a forest garden to allow plenty of patches where ample light reaches the ground so that a wide variety of plants can grow even though the trees and shrubs will cast some shade.

Because incorporating edge into a design enhances diversity, I like to build lots of curves into my beds instead of straight lines. It’s simple math— if a straight line is the shortest distance between two points, then a curving line must be a longer edge.

Maximizing Solar Absorption in Your Forest Garden

Edges also provide opportunities for light to illuminate the lower levels of plantings. To make sure plenty of light can reach into my forest garden, I designed it with wide, curving access routes around and between collections of plants. I also included patio areas with rounded edges to open up space for light to penetrate. Opening up a planting for more light to penetrate contributes to maximizing solar absorption.

This is important for gardens in general because sunlight is the energy source for photosynthesis. Photosynthesis fuels the growth of plant tissues and also the microbiome—the community of fungi, bacteria, and a wide range of other organisms in the soil that all contribute to keeping soil healthy and functioning. And the warmth of the sun is especially important for the ripening of fruit, so the more light that penetrates into all layers of your forest garden, the more evenly and successfully your fruit will ripen.

Utilizing the Vertical Dimension

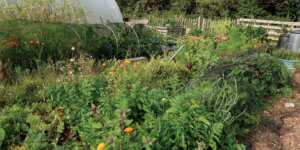

It’s possible to incorporate all seven layers even in a small plot. Here six layers occupy no more than 25 square feet (2.3 sq m). Overstory: honey locust, top center. Understory: apricot, center. Shrub: clove currant, left; red currant, right. Herbaceous: Russian comfrey, foreground.

In addition to creating abundant edges to allow light into the garden, you can maximize solar absorption by utilizing the entire vertical dimension. Typical home landscape plantings don’t do this, but your goal should be to capture all of the available sunlight. To accomplish this, design your garden to take advantage of as much vertical space as your plot allows.

The Seven Layers of A Forest Garden

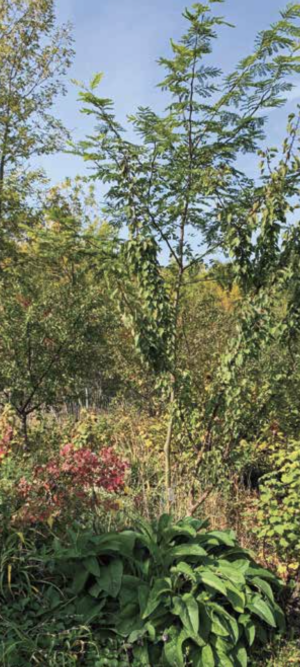

In a forest garden, vertical space can be divided into seven layers that overlap in an organic way.

- The overstory includes the tallest plants, those that grow to 30 feet (9 m) or taller. Black locust and walnut trees are examples of overstory plants.

- The understory contains trees that reach between 10 and 30 feet (3–9 m) tall. This includes most fruit trees and some nuts.

- The shrub layer ranges from 3 to 12 feet (1–3.5 m) above the soil surface. In this layer you’ll find brambles, berry bushes, and other woody plants.

- The herbaceous layer, from 2 to 10 feet (60 cm– 3 m) above ground level, contains perennial plants with succulent stems that die down to the ground as the weather cools in the fall. These plants then re-sprout each spring. Examples are most perennial vegetables, flowers, and some herbs.

- The ground cover layer is close to the soil surface. These are the clumping, running, suckering, and sometimes vining herbaceous plants that grow up to 2 feet tall and cover the soil. Examples include strawberries, violets, and clovers.

- The root layer includes plants that have edible parts growing in the vertical space below the soil surface. Edible licorice and sunchoke are examples.

- The vine layer can occupy all levels of vertical space. For instance, grapes and wisteria can climb as high as a tree is tall, if they have strong enough support. Other vines such as perennial sweet pea will self-limit their height to about 10 feet. All vines will trail over the ground if there is nothing nearby to climb up.

Some permaculturists add an eighth layer, which consists of fungi. The fungus layer includes edible mushrooms, such as oyster and shiitake.

How Many Layers Should You Incorporate?

Depending on the size of your garden, aim to incorporate as many of these layers as you can. If your space is restricted to a small plot, your edible forest might be made up of shrub, herbaceous, and ground cover layers only, with no overstory or understory trees. In Paradise Lot, permaculturists Eric Toensmeier and Jonathan Bates describe how they omitted the overstory when they planted a permaculture garden on a 1/10-acre (405 sq m) city lot. They focused their attention on fruit trees as the tallest layer and then wove in all the other layers beneath.

Adding More Layers to Your Forest Garden

During dry spells, plants on this hügelkultur mound (under construction) will be able to reach water absorbed and stored by the decaying wood in the mound’s base layer.

In some situations, layers can be added later in time as conditions permit. For instance, at first there might be no trees tall enough to serve as trellises for vines, or no shady spots in which to grow mushrooms. Wait until the overstory matures, and then add vines and mushrooms.

I planted trees the first year of my garden’s development, and then waited three or four years to add shade-adapted vines and ground covers beneath them. In another instance, several years after I planted understory fruit trees, I planted more trees nearby that would eventually surpass the fruit trees in height to occupy the overstory layer above them.

In addition to utilizing as many vertical layers as possible, you can maximize absorption of solar radiation by planting the tallest trees on the north side of a garden. This will minimize the amount of shade they cast on other garden plants. Reserve the sunniest spots in your garden for the plants that need the most sun, place those that can tolerate shade in the shadier spots, and incorporate wind- breaks to slow or divert the wind and thus preserve heat.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Get one step closer to the forest garden of your dreams by creating a plant grouping! These arrangements of plants help contribute to a thriving food forest.

Read MoreNow is the perfect time to start planning your garden. The location of your planting site is key to a thriving garden and one of the first things to consider!

Read MoreDitch the chemicals and let flowers do the work! Planting certain flowers near gardens can be your go-to solution for keeping pests at bay. Plant these flowers for a pop of color & make pest control seem easy!

Read MoreSeed savers raise your hands! Picking the right seeds can make or break your garden. Learn some easy tips on how to choose the best seed crop for a thriving garden.

Read MoreMushroom lovers, raise your hands! Ever get weird looks when you say you’re into mushrooms? “So, are you into magic ones?” But we know the truth: all mushrooms are magical. Discover the fascinating world of mushrooms!

Read More