The Hunt for Huckleberries (Plus A New Recipe!)

Huckleberries are a true prize for fruit foragers. Describing them as “intense, juicy, and addictive,” author Sara Bir has the lowdown on where and how to harvest them.

And if you’re one of the lucky ones who brings home a bountiful harvest, the recipe below for Buckwheat Huckleberry Buckle is a MUST-make. Trust us.

The following excerpt is from The Fruit Forager’s Companion by Sara Bir. It has been adapted for the web.

The Wild Huckleberry

Vaccinium spp. Ericaceae family. Found throughout Canada; northern and western US.

Huckleberries are wild through and through, and a certain type of person with a fierce independent streak and a love of self-sufficiency sees huckleberries as an emblem of a western way of life. Northwestern Montana is known for its huckleberries, as are Washington and Oregon. It’s the state fruit of Idaho. Species grow all the way up the Pacific Coast to Alaska.

Everyone has heard of huckleberries, but relatively few actually get to taste them. They are true foragers’ delights, and it is unwise to describe them as similar to blueberries around a huckleberry hound, because you will get an earful. Huckleberries have a more prominent “belly button” on their blossom ends than blueberries do. While blueberries can grow in clusters of several berries, huckleberries stud branches one by one, asking your fingers to be more nimble. And most important, huckleberries taste like huckleberries: intense, juicy, addictive.

The huckleberry hunt can get competitive, but there is a precedent for working things out. Huckleberries were at the heart of a treaty between the Yakima Nation and the US National Forest Service. The contested huckleberries were in Gifford Pinchot National Forest, about 100 miles (160 km) south of Seattle. The Yakima have foraged for huckleberries on the land for generations — to them, the annual picking and preserving of berries is a culturally, socially, and spiritually significant event — but during the Great Depression, outsiders began showing up and stripping the berries, too.

The huckleberry hunt can get competitive, but there is a precedent for working things out. Huckleberries were at the heart of a treaty between the Yakima Nation and the US National Forest Service. The contested huckleberries were in Gifford Pinchot National Forest, about 100 miles (160 km) south of Seattle. The Yakima have foraged for huckleberries on the land for generations — to them, the annual picking and preserving of berries is a culturally, socially, and spiritually significant event — but during the Great Depression, outsiders began showing up and stripping the berries, too.

In 1932 forest supervisor J. R. Burkhardt met with council members and eventually set aside 2,800 acres (1,135 ha) for tribal use during huckleberry season. The agreement was bound with a handshake and eventually written into the forest’s management plan. It is still in effect today, though reputedly some non–Native Americans choose not to heed the signs posted and harvest huckleberries freely.

Huckleberries and Hiking: A Dynamic Duo

Speaking of national forests, huckleberries and hiking go hand in hand. While out on unrelated mountain or meadow adventures, you can scout out promising spots to return to. Serious pickers think nothing of going to higher elevations to get the best ones. The deeper the season, the higher you go.

Huckleberries are not big, and to pick many is a legitimate outing. Because huckleberries thrive on slopes, harvesters must be intrepid. There is brush to get through and footing to maintain. A fall could mean spilling your container, a small tragedy. Transfer your open container to a lidded container or zip-top bag every now and then, so if you do slip, your loss will be minimized.

The bushes can be low, or grow up to 6 or 7 feet (1.8 to 2.1 m) tall. Some people spot huckleberries on the side of a road, a sign that there are probably more huckleberries up higher. Pull over and check it out! If it’s been cleared of berries already, there may be other bushes farther off the road to investigate.

Forest fires are part of what make huckleberries grow, though it’s a slow cycle. Since huckleberries like full sun, they eventually establish themselves in open areas left after a burn. There’s a push-pull of vegetation as the forest begins to encroach on its old territory, and Native Americans would some times burn trees and brush to preserve huckleberry fields.

Most species of huckleberries are dark purple-blue-black when ripe, but red huckleberries (V. parvifolium) are red when ripe, and rumored to be more tart than black ones. After one taste, you’ll know!

Storing Huckleberries

Ripe berries are plump, sweet, and dark purple. They are soft, so pick them one at a time.

Ripe berries are plump, sweet, and dark purple. They are soft, so pick them one at a time.

Pick out any debris once you get home, but don’t rinse the berries until you use them. Some huckleberry fans don’t rinse them at all, because it will wash off precious juice.

Zip-top bags don’t provide much cushioning, but they do contain any leaking juices. If you want intact berries, bring a rigid container.

Freeze huckleberries within a day of harvesting them. They get softer as they sit, and if frozen they form a block and thaw into mush after releasing more liquid — still usable for some recipes, but not always the desired effect. Par-freeze the berries on a rimmed baking sheet before bagging them so you can pull out individual frozen berries and drop them directly onto rounds of griddling pancake batter.

Culinary Possibilities

Huckleberries release their juice easily, so use them in ways that take advantage of this. Gooey jams and gushy baked desserts are obvious here. Anyone who’s browsed in a Rocky Mountain or Pacific Northwest gift shop has doubtlessly seen plastic bears filled with huckleberry-infused honey. Quick-cooked ketchups and sauces for game bring it to the savory side.

RECIPE: Buckwheat Huckleberry Buckle

Yield: 8-10 Servings

We reserve buckwheat for pancakes and blinis, which is a shame. Buckwheat flour has a strong but sophisticated flavor — a little nutty, a little fruity. It goes well with berries in this buckle — a rustic fruit dessert so named because the berries make the cake buckle in its center. Think of it as a giant muffin. I love this at breakfast, or as a midday snack.

Ingredients

- 1/2 cup (50 g) rolled oats

- 1/4 cup (45 g) buckwheat flour

- 1/2 cup (110 g) packed light brown sugar

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- Pinch freshly grated nutmeg

- 1/4 cup (1/2 stick) unsalted butter, cut into small pieces and at room temperature

For the cake

- 1-1/4 cups (160 g) unbleached all-purpose flour

- 1/2 cup (90 g) buckwheat flour

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1/4 teaspoon baking soda

- 1/4 teaspoon table salt

- 6 tablespoons unsalted butter, at room temperature

- 3/4 cup (150 g) granulated sugar

- 2 large eggs

- 2/3 cup (160 ml) buttermilk

- 3 cups (435 g) huckleberries

Procedure

- Preheat the oven to 350 degree Fahrenheit and set the rack in the middle. Grease a 9 × 9-inch (23 × 23 cm) pan.

- Make the streusel: Combine the oats, buckwheat, brown sugar, salt, nutmeg, and butter in a medium bowl. With your fingertips, work the mixture until it’s crumbly. Set aside.

- Make the cake: In a medium bowl, whisk together the ingredients from flour through the salt.

- In the bowl of an electric mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, beat the butter and granulated sugar on medium-high speed until lightened, about 2 minutes.

- Add the eggs one at a time, scraping down the bowl after each, and beat until fluffy, about 3 minutes.

- Mix in the flour mixture in three additions, alternating with the buttermilk.

- Fold in half of the huckleberries.

- Spread the batter in the prepared pan. Scatter the remaining berries over the top, then the streusel.

- Bake until a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean, about 40 minutes.

- Cool on a rack for at least 10 minutes before serving.

- Covered with plastic wrap, the buckle will keep for up to 2 days.

Also try with: Blueberries, mulberries, blackberries, raspberries.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

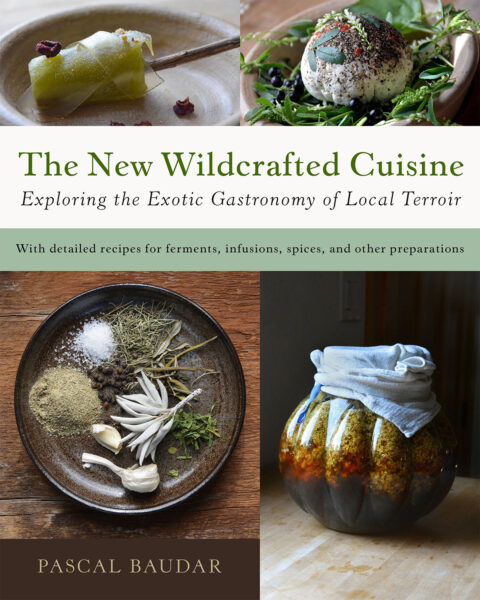

Chances are, you’ve seen cattails growing on the edge of your local lake or stream at least once or twice. Instead of just passing these plants, try foraging for and cooking them to create delicious seasonal dishes! The following excerpt is from The New Wildcrafted Cuisine by Pascal Baudar. It has been adapted for the…

Read MoreGarlic mustard: while known as “invasive,” this plant can be consumed in its entirety and has great nutritional value. Plus, the garlic-flavor is a perfect addition to any recipe that calls for mustard! The following are excerpts from Beyond the War on Invasive Species by Tao Orion and The Wild Wisdom of Weeds by Katrina…

Read MoreOh, honeysuckle…how we love thee. If only there was a way to capture the sweet essence of this plant so we could enjoy it more than just in passing. Luckily, foraging and some preparation can help make that happen! Here’s a springtime recipe that tastes exactly like honeysuckle smells. The following excerpt is from Forage,…

Read MoreIntroducing…your new favorite brunch dish! This whole broccoli frittata is packed with fresh, wildcrafted flavors that are bound to help you start your day off on the right foot. The following is an excerpt from The Forager Chef’s Book of Flora by Alan Bergo. It has been adapted for the web. RECIPE: Whole Broccoli Frittata…

Read MoreWondering where to forage for greens this spring? Look no further than hedges, which serve as natural havens for wild greens and herbs! The following is an excerpt from Hedgelands by Christopher Hart. It has been adapted for the web. Food from Hedges: Salads and Greens Let’s start by looking at all the wild foods…

Read More