Seed as a Common Resource: Crops and the People Who Nurture Them

The following excerpt is from The Accidental Seed Heroes by Adam Alexander. It has been adapted for the web.

Nature, ere she gives up, makes a violent effort to reproduce.

—Isaac Anderson-Henry, Transactions of the Botanical Society (1867)

The landscape was green, the terraces sculpturing the rolling hills and mountains with their human imprint. At 2,000 metres elevation and 5 degrees north of the equator, the air was warm and fresh from recent rains – the grey clouds, like brooding monsters, scuttling across the sky. In that moment, a more perfect climate for growing crops seemed hard to imagine. On this convivial Sunday morning my lovely driver, Ermias, had dropped me and local guide Genale Geyato at his village, Mecheke. It nestles in the centre of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Konso Cultural Landscape in southern Ethiopia, and what this most beautiful of regions has to teach us all about sustainable agriculture and plant breeding cannot be overestimated.

I had come to this remote corner of the country to see how traditional agroforestry is practised and how the genius and hard work of the farmers have ensured a resilient and stable food supply for the last eight hundred years.

The indigenous people of this region maintain and cultivate their crops in a land of terraces.

In all of those eight centuries, despite the fact that the soil is thin and requires constant husbanding, Genale told me they have never once suffered from famine, nor have they had their land degraded by erosion due to drought or flood. As we strolled along the narrow paths and among the round mud and thatch houses of Genale’s tribe, an old lady carrying a bouquet of deep purple sorghum seed heads slung over her shoulder – destined to be turned into a refreshing and tasty alcoholic beer I was soon to savour – walked past us as a gaggle of curious kids gathered around.

What the farmers tending to their terraces told me about maintaining the genetic diversity of their crops, about living in a world of food insecurity where the smallest deviation in the weather – rain coming too early or too late, or there being too much or too little of it – could prove fatal, left me humbled and in awe.

As with other indigenous farmers around the world, I sit at their feet. That admiration, coupled with a curiosity to understand more about the choices we have in how we develop and maintain the crops that will nourish all of us as our climate changes, and a wish to acknowledge their wisdom and skill, has led me to write this book. The farmers in this region have been selecting, improving, maintaining and celebrating the seeds of their harvests for centuries; theirs is just one example of how different approaches to plant breeding offer more hopeful routes to a future where we can feed ourselves, and not at the planet’s expense.

In my previous book, The Seed Detective, I told the stories of many vegetables’ journeys from wild parent to cultivated offspring and their place as history on a plate. In this book, I don my seed detective homburg once more to uncover the remarkable stories and check out the flavours of a new generation of crops that exist because of a passionate and committed cohort of breeders and growers, both traditional and modern, around the world.

They are showing the way forward, not only championing traditional varieties, but breeding delicious new ones that are fundamental to a sustainable future for our planet. Meeting these people and savouring the delights of their creations, I am filled with a sense of optimism.

We can and do breed crops that will feed us as our climate becomes ever more extreme and unpredictable – and that are not dependent on chemical inputs, monoculture and uniformity. Maintaining and improving traditional crops and breeding new cultivars that do best in low-input growing systems – ones that require little or no use of chemical fertilisers in order to flourish – and that are seen as a public good should be our mantra. They should stay firmly in the hands of indigenous farmers, independent local breeders, and eccentric, obsessive and passionately committed amateurs and professionals who believe in freely sharing their work.

PHOTO CREDIT: Jesse Alexander

The world needs this essential counter to the hegemony and hubris of a globalised and commodified system because, since the middle of the twentieth century, plant breeding has been focused on creating cultivars that are designed to deliver greater yields within a system of monoculture. This has created an existential threat for us all because this system has bred out diversity and resilience within our most important crops, with failures due to climate change, pests and diseases.

As we shall see, embracing a diverse and holistic approach to breeding is fundamental to ensuring nutritious and plentiful harvests in a changing climate, drawing on the best of science, invention, curiosity and our deep, past knowledge. Not to mention the pursuit of deliciousness. The characters that feature throughout this book – the crops and the people who nurture them – inspire solutions to breaking the current model, in which seeds are considered to be intellectual property, controlled by patents and owned by a handful of giant agribusiness monopolies. I cherish seed as a common resource that all the world should be able to access freely.

Seeds reinforce our diverse cultural identities, and a celebration of the place of plant breeding, in all its forms, lies within the stories in the following pages.

In talking about different cultures and parts of the world, one of the challenges has been to avoid lumping entire regions into binary categories in order to describe their approaches and philosophies towards breeding and maintaining the crops we rely on to survive. Terms like the West and the East, the developed or developing world and others, which some might consider pejorative, are all describing economic activity and status.

Over the years, they have created much noise, misunderstanding and debate. Although they are far from being perfect because of their use within an economic context, I have chosen to use the terms Global South and Global North to describe a particular reality: where homogenous monoculture farming is practised extensively – but not exclusively – in the wealthiest countries of the northern hemisphere and the antithesis of this approach is seen to be employed more extensively – but also not exclusively – in the southern hemisphere. I do not use these terms as economic indicators.

A Changing Climate in Plant Breeding

‘You’re an accidental plant breeder whether you think so or not!’ said Carol Deppe, the godmother of American plant breeders and author of the plant breeder’s bible, Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties. I had been in touch with her as I embarked on writing this book because plant breeding was a subject I knew virtually nothing about. I was keen to understand something about the work of the Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI), which was founded in the US in 2012. At the time of writing, Carol is its chair, and their mission is ‘maintaining fair and open access to plant genetic resources worldwide in order to ensure the availability of germplasm [seeds] to farmers, gardeners, breeders, and communities of this and future generations’.

Up till this point, in the thirty-five years I had spent collecting, saving and sharing seeds, I had presumed all I was doing was maintaining varieties, ensuring that the seed I saved was the same as the seed I had sown. I hadn’t thought that continually selecting seeds from the first fruits and pods to ripen was a form of plant breeding; that varieties I had been saving over many generations and that were very happy growing in my corner of South Wales had become locally adapted – so-called landraces, or farmers’ or folk varieties (FVs). According to Carol, I now qualify as a backyard breeder because the decisions I make about the seeds I save mean my crops change too.

Since the middle of the twentieth century, a combination of highly mechanised farming, continuous cropping with monocultures and increased dependency on high-yielding homogeneous cultivars of the three most important crops in the world – wheat, rice and maize – has resulted in a 90 per cent reduction in the genetic diversity of our food.

Just five giant agribusinesses breed and sell 40 per cent of all the seed in the world.

Their business models perpetuate the use of monoculture as the solution to producing more food at the expense both of greater diversity and innovation and of small, local and highly adaptive breeding. Dependency on homogeneous, genetically narrow cultivars that are grown as monocrops is a high-risk strategy. A single pathogen can wipe out swathes of crops because all the plants are identical and any chink in their genetic armour is easily exploited.

A warming world is creating an ever more benign environment for new and deadly pathogens and pests to evolve. As I hope to show, although there is a place for this form of modern food production in certain places, as a model it needs to be replaced with a suite of solutions that ensure innovation puts people and planet first.

So, as we enter the second quarter of the twenty-first century, can we realistically look forward to a point in the next twenty-five years where plant breeding is no longer a monopoly?

Is the tide turning? I believe there are compelling reasons to be hopeful.

Indigenous and traditional farmers from the Global South, hobby farmers, academic institutions, amateur and professional breeders with an emphasis on seeds best suited to organic growing, frequently working together, are maintaining, developing and breeding new cultivars that are fit for purpose: crops that are nutritionally dense, delicious, need less water and can cope in more extreme climatic conditions. Driven by altruism and collaboration, these people are working with wild relatives, local varieties, FVs and older commercial varieties.

For the most part, their new varieties are open-pollinated – pollinated by wind or animals – and ‘breed true’, meaning the progeny are identical to the parent and the grower knows the seeds in the packet are what the packet says they are! Using a combination of traditional methods and technologies, alongside a diverse number of approaches and local solutions to restore food security – the ability to feed ourselves in the face of regional or global conflict, weather disasters and with less dependence on a globalised food system – means we really can improve not only our health but the planet’s too.

I look at the diverse approaches to plant breeding that are employed across many different species and types of crop. They fall into two distinct types.

The first is phenotype breeding, which is based on considering a plant’s morphology – its observable characteristics – transferring pollen from a male flower to a female one (usually with a small brush), a technique first used by botanists and scientists three hundred years ago.* Phenotype breeding also includes mutagenesis, the forced mutation of a plant using either chemicals or radiation, a popular and successful breeding method that has been in place for at least one hundred years.

The second type is genotype or molecular breeding. This includes transgenics: the transfer of genes from one species into another, which is the basis of all forms of genetic modification. This is different from genetic engineering orgenome editing, which is the transfer or removal of genes between individual plants of the same species.

In the same way that when I am fertilising a courgette flower I use a paintbrush to transfer pollen from a male to a female plant, geneticists (modern plant scientists) use the equivalent of a pair of scissors or a scalpel to edit genes within an organism’s DNA. Another tool is marker-assisted selection, also known as marker-aided selection or MAS. This is a technology that looks at DNA-based genetic markers within a plant’s genome – its genetic barcode – and identifies those that are associated with specific traits the breeder wants to include in their new cultivar. MAS has, until now, been used almost exclusively by geneticists.

However, with genetic sequencing facilities at universities being made more widely available, conventional breeders are starting to use this amazing tool to speed up selections of varieties employing classical phenotype breeding. It is democratising plant breeding in the Global South, especially with so-called ‘orphan crops’, which feature in many of the following chapters.

We don’t all need to become backyard breeders or even, like me, accidental ones; as growers, we don’t even need to eschew many of the modern hybrid cultivars our seed catalogues are stuffed with.

As citizens I am not suggesting we boycott those same uninspiring specimens that populate our supermarket shelves – though you won’t catch me buying them. After all, it should be first and foremost a matter of personal choice what we decide to grow and eat. I just want that choice to be better informed and infinitely more diverse and enjoyable. But will new, independently developed strains of fruits, vegetables and grains sustain us all, not just with nutritious and delicious food, but as part of the solution to combating climate change and returning fertility to our soils and biodiversity to our land? I passionately believe they will.

My quest to find and savour the crops that can and must be part of building diverse, resilient and nature-friendly solutions to feed the world has taken me to Rajasthan, the US, my own backyard in Wales, across Europe to the remote regions of southern Albania, and into the southern part of the Great Rift Valley of Ethiopia.

Throughout my travels, I have come face to face with crops as exotic as they can be prosaic: lettuce, peppers and chillies, aubergines, wheat, onions, beans, peas and tomatoes. Also, indigenous crops, such as enset, tef and sorghum – staples for millions in the Global South – and traditional cereal mixes known as maslins, which provide resilience and a harvest in the face of extreme climate events. Finally, I include one of the most important and delicious of fruits that exemplifies the challenges and complexities in different approaches to breeding: the apple.

A Taste for an Identity

What do you recommend I grow?’ It’s the one question above all others that people ask me. Impossible to answer without knowing something about the poser of the question. My first response is always, ‘What do you like to eat?’

This is as much to tease out what matters to them on both a culinary and a cultural level as to understand the circumstances under which they are planning to breed, grow and consume their beloved crops. This matters because feeling a connection to our food – its provenance, its place in our own stories and identity, its flavours and uses – becomes the starting point on a journey where we care.

I care very much because I feel connected to what I grow and eat.

I believe that the route to a healthier world is to celebrate foods that are local to us, that enhance biodiversity and have natural resilience to pests and diseases: crops that can evolve and cope with the inevitable extremes of a changing climate. All of us who grow vegetables and save seeds are part of the solution, whether we like it or not!

I feel empowered by my association and connection with varieties that matter to me; not only because they benefit me nutritionally and taste great, but because they connect me to a positive journey towards a more sustainable and healthy world. It goes without saying that it all starts with seeds – those that evolve and adapt as we and our world do.

Seeds strengthen our connections to what we grow and eat; they are intrinsic to our identity and our future.

So, the first questions I ask those you will meet in the following pages are, ‘Is it delicious?’ and ‘Why is it important to you?’ Two things that we might also ask ourselves and that have led me on a journey to discover how many exciting, inspiring and empowering people there are out there; people who offer hope and insights into a future for our world that is rich with flavour and amazing foods: a solution to a carbon-neutral planet by mid-century.

I hope that sharing this journey with me will instil in you the same feelings of hope I have that great things in the field of food production are already making the world a better place for all living things.

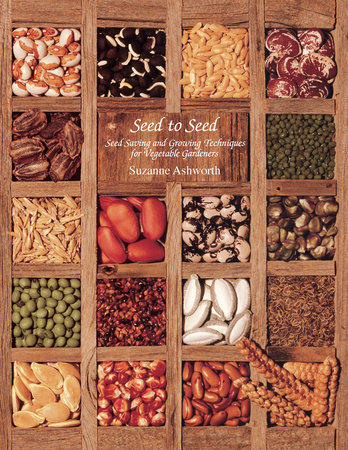

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

When you save seeds, you become a plant breeder! Take control of your seeds and grow the best traditional and regional varieties and even develop your own.

Read MoreFire Cider is great for stimulating digestion and warming you up from the inside out, no matter the season. This beverage can be prepared in water or tea as desired.

Read MoreEmbracing the tradition of saving seeds is a powerful practice for both home gardeners and seasoned horticulturists alike.

Read MoreLooking to add another recipe to your fermenting repertoire? Try your hand at Kvass. Bonus: it is the perfect entry-level project. This nourishing beverage calls for just a few simple ingredients and only takes a couple of days to ferment.

Read MoreThe Netherlands is ranked second in agricultural export volume behind the United States. Their secret weapon? Greenhouses and hoophouses.

Read More