The Complexity of Membranes and the Beauty of the Unseen

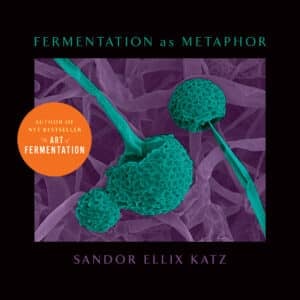

It can be comforting to define things using strict categories; black and white, tasty or gross, good or evil. Sandor Ellix Katz, author of Fermentation as Metaphor, knows that this isn’t really the case in real life. Taking another lesson from the act and art of fermentation, Katz dives into the complexity of membranes and human diversity.

The following is an excerpt from Fermentation as Metaphor by Sandor Ellix Katz. It has been adapted for the web.

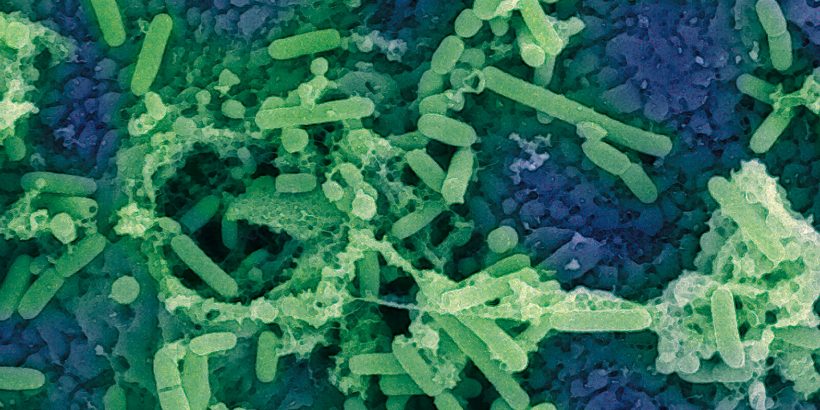

(Miso under scanning electron microscope. Copyright 2019 MIMIC)

It can be appealing to think of certain things in stark, absolute categories. There’s good and bad, hot and cold, clean and dirty; there’s kindness and cruelty; there’s Heaven and Hell. In political reporting we hear about red states and blue states, though everywhere there is a diversity of opinion, even where the vast majority feels one way or another. In most contexts gender is seen as male or female, despite the fact that most of us embody some blend of masculine and feminine aspects, and despite the presence everywhere of people who do not neatly conform to one or the other. In reality most things are not black or white; they exist as in-between shades of gray, or really all over the color spectrum.

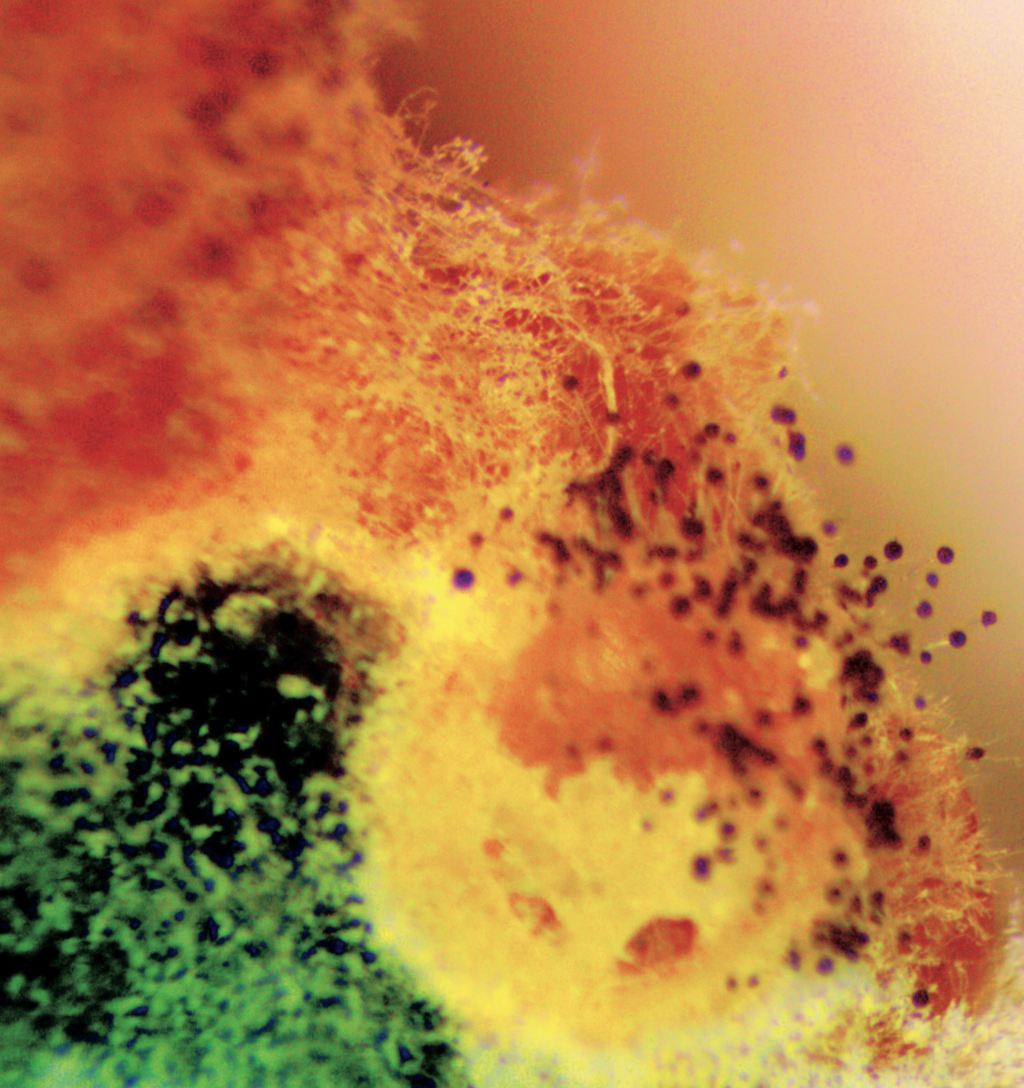

Moldy Millet under Stereoscope. Photography by Sandor Ellix Katz

If categories can never be absolute, then neither are edges, boundaries, or membranes. Consider our skin: It is an edge that separates that which is within us from that which is outside us. Yet sunlight absorbs into it; sweat and sometimes blood and pus come out of it; mosquitoes and countless other creatures can pierce it; infections, toxins, and other conditions can cause it to rot; heat and cold and many chemicals can burn it; and bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms inhabit every bit of it, existing in elaborate, dense communities that vary with the environmental conditions of different parts of our bodies. The skin on each of us, which we think of as the boundary between ourselves and the world beyond, is home to many more microbes than there are humans on the Earth, and these microscopic beings, in symbiotic relationships with us as well as one another, spin elaborate biofilms, constantly exchange metabolic by-products as well as genes, and mediate much of our interaction with the world around us. Even beyond our skin, each of us is host to a microbial force field, a unique microbial signature that emanates with our body heat.1

Our skin, like the membranes of every living organism and cell (in fact, like all borders, membranes, and edges), is complex. From a distance, or in the abstract, these edges may appear to be sharp, hard dividing lines. But up close they are textured, supporting a multitude of smaller structures, biodiverse and selectively permeable.

All along, throughout our long evolutionary history, this complexity and biodiversity has been with us, though the extent of it has been and remains something of a mystery. Many people in our time, even with the benefit of current scientific understanding, continue to regard microorganisms in general as mortal enemies. As I complete this book, in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for chemical sanitizing products is greater than ever, as people desperately seek to avoid contact with the novel coronavirus in order to slow its spread. This is vitally important, and I am trying like most everyone to isolate, distance, wash my hands frequently, and strategically reduce my risk of exposure. But realistically, all we can do is slow transmission, because eventually, inevitably, nearly all of us will be exposed.

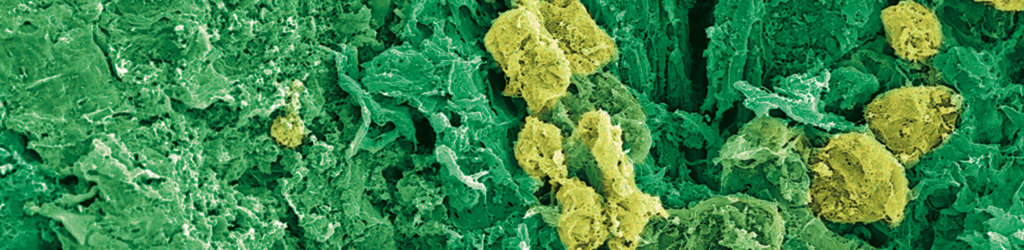

Doubanjang under scanning electron microscope. Copyright 2019 MIMIC

Our existential context is a microbial matrix. We are continually learning more about how critically important the vast microbial populations everywhere are, not only bacteria but also fungi, viruses, and all the others. Forms of life are not bad or good; we exist in all our co-evolved complexity, a vast matrix of intertwining life-forms at different scales, interacting, mutually coexisting, and feeding off one another, in ways we are just beginning to recognize.

Mutual coexistence, however perceived (or not), shapes cultural evolution, and since prehistoric times people have learned to work with invisible life forces, such as bacteria and fungi, in the context of fermented foods and beverages, as well as agricultural methods, fiber arts, animal husbandry, and more. Human cultures around the world have recognized the invisible force of fermentation in mystical ways, as reflected in the gods and goddesses and mythical figures, and the stories and ritual ceremonies found in diverse traditions. There is even speculation that Amerindian healers may have perceived microbes and guided Western science to investigate their role.2

But only with increasingly sophisticated tools have we begun to witness and comprehend the complexity of the ecosystems upon, within, and all around us. From Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s seventeenth-century descriptions of animalcules, via Louis Pasteur’s nineteenth-century innovations in microbial identification and isolation, to modern DNA sequencing and a multitude of new microscopy technologies, we have been able to grasp more clearly, as well as see more vividly, the brilliant diversity of life.

- James F. Meadow et al., “Humans Differ in Their Personal Micro- bial Cloud,” PeerJ 3 (September 2015): e1258, https://doi.org /10.7717/peerj.1258.

- César E. Giraldo Herrera, Microbes and Other Shamanic Beings (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018).

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Introducing…your new favorite brunch dish! This whole broccoli frittata is packed with fresh, wildcrafted flavors that are bound to help you start your day off on the right foot. The following is an excerpt from The Forager Chef’s Book of Flora by Alan Bergo. It has been adapted for the web. RECIPE: Whole Broccoli Frittata…

Read MoreWondering where to forage for greens this spring? Look no further than hedges, which serve as natural havens for wild greens and herbs! The following is an excerpt from Hedgelands by Christopher Hart. It has been adapted for the web. Food from Hedges: Salads and Greens Let’s start by looking at all the wild foods…

Read MoreThere’s a whole new world out there when it comes to koji. It doesn’t matter if you’re making bread, cheese, or ice cream, koji helps you pump up the flavor! Growing Koji in Your Own Kitchen Koji, the microbe behind the delicious, umami flavors of soy sauce, miso, fermented bean sauce, and so many of…

Read MoreWhether you’re looking to replace your end-of-the-day cocktail, relax before bed, or want something new to add to your tea, this non-alcoholic mocktail syrup base will do the trick. Delicious and all-natural, take a sip of this nightcap mocktail and feel your troubles melt away. The following is an excerpt from Herbal Formularies for Health…

Read MoreWant to enjoy bread without worrying about gluten? With Einkorn bread, a light bread with the lowest glycemic index, you can still enjoy all of the delights of bread. without any of the allergic reactions! The following is an excerpt from Restoring Heritage Grains by Eli Rogosa. It has been adapted for the web. Einkorn…

Read More