Eliot Coleman’s Components of the Winter Harvest

So you want to start reaping a winter harvest, but you’re not sure where to start?

Eliot Coleman breaks down the three basic components of the winter harvest so that this time next year, you’ll be knee-high in produce! (Maybe not knee-high, but you’ll definitely have fresh vegetables!)

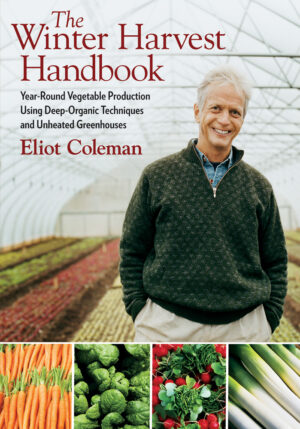

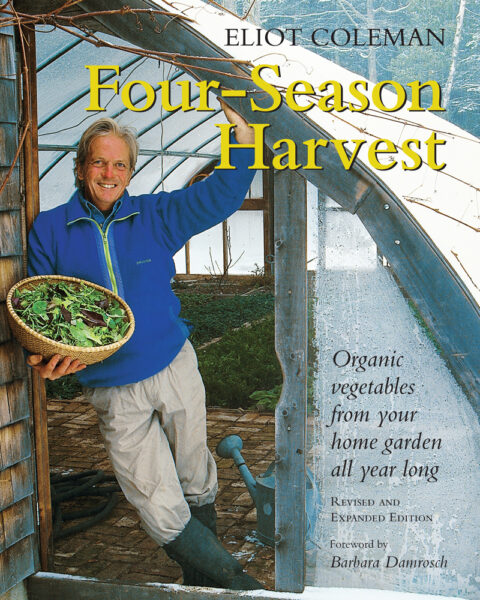

The following is an excerpt from The Winter Harvest Handbook by Eliot Coleman. It has been adapted for the Web.

The Winter Harvest: Three Components

The winter harvest, as we practice it at Four Season Farm, has three components: cold-hardy vegetables, succession planting, and protected cultivation.

1. Cold-Hardy Vegetables

Cold-hardy vegetables are those that tolerate cold temperatures.

They are often cultivated out of doors year-round in areas with mild winter climates. The majority of them have far lower light requirements than the warm-season crops.

The list of cold-hardy vegetables includes the familiar—spinach, chard, carrots, scallions—and the novel—mâche, claytonia, minutina, and arugula.

The list of cold-hardy vegetables includes the familiar—spinach, chard, carrots, scallions—and the novel—mâche, claytonia, minutina, and arugula.

To date there are some thirty different vegetables—arugula, beet greens, broccoli raab, carrots, chard, chicory, claytonia, collards, dandelion, endive, escarole, garlic greens, kale, kohlrabi, leeks, lettuce, mâche, minutina, mizuna, mustard greens, pak choi, parsley, radicchio, radish, scallions, sorrel, spinach, tatsoi, turnips, watercress—which at one time or another we have grown in our winter-harvest greenhouses.

The eating quality of these cold-hardy vegetables is unrivaled during the cooler temperatures of fall, winter, and spring. They reach a higher level of perfection without the heat stress of summer.

2. Succession Planting

Succession planting means sowing vegetables more than once during a season in order to provide for a continual harvest.

The choice of sowing dates, from late summer through late fall, and winter into spring, keeps the cornucopia flowing. In midwinter the vigorous regrowth on cut-and-come-again crops provides the harvest while late-fall-and-winter-sown crops slowly reach productive size.

We begin planting the winter-harvest crops on August 1, the start of what we call the “second spring.”

We continue planting through the fall. The reality of sowing for winter harvest is that the seasons are reversed from the usual spring-planting experience. Day length is contracting rather than expanding; temperatures are becoming cooler rather than warmer.

Success in maintaining a continuity of crops for harvest through the winter is a function of understanding the effect of shorter day length and cooler temperatures on increasing the time from sowing to harvest.

Thus the choice of precise sowing dates for fall planting is much more crucial than for spring planting. The dates are also very crop specific.

We aim for a goal of never leaving a greenhouse bed unplanted, and we come pretty close. Within twenty-four hours after a crop is harvested, we remove the residues, re-prepare the soil, and replant. We keep careful records so as to follow as varied a crop rotation as possible.

3. Protected Cultivation

Protected cultivation means vegetables under cover.

The traditional winter vegetables will often survive outdoors under a blanket of snow. Since gardeners can’t count on snow, the best substitute is shelter of an unheated greenhouse.

The traditional winter vegetables will often survive outdoors under a blanket of snow. Since gardeners can’t count on snow, the best substitute is shelter of an unheated greenhouse.

Many delicious winter vegetables need only that minimal protection.

Our winter-harvest cold houses are standard, plastic-covered, gothic-style hoop houses. The largest of our houses are 30 feet wide and 96 feet long.

They are aligned on an east-west axis. For the most part the cold houses need only a single-layer covering of UV-resistant plastic, whereas heated greenhouses benefit from two layers, which are air-inflated to minimize heat loss.

The success of our cold houses seems unlikely in our Zone 5 Maine winters where temperatures can drop to –20˚F (–29˚C). But our growing system works because we have learned to augment the climate-tempering effect of the cold house itself by adding a second layer of protection.

We place floating row-cover material over the crops inside the greenhouse to create a twicetempered climate. The soil itself thus becomes our heat-storage medium, as it is in the natural world.

Any type of lightweight floating row cover that allows light, air, and moisture to pass through is suitable for the inner layer material in the cold houses.

The row cover is supported by flattopped wire wickets at a height of about 12 inches (30 cm) above the soil. We space the wickets every 4 feet (120 cm) along the length of 30-inch-wide (75 cm) growing beds.

The protected crops still experience temperatures below freezing, but nowhere near as low or as stressful as they would without the inner layer. For example, when the outdoor temperature drops to –15˚F (–26˚C), the temperature under the inner layer of the cold house drops only to 15˚F to 18°F above zero (–10˚C to –8°C) on average.

The cold-hardy vegetables are far hardier than growers might imagine and, in our experience, many can easily survive temperatures down to 10˚F (–12˚C) or lower as long as they are not exposed to the additional stresses of outdoor conditions.

The double coverage also increases the relative humidity in the protected area, which offers additional protection against freezing damage.

The climate modification achieved by combining inner and outer layers in the cold houses is the technical foundation of our low-input winter-harvest concept.

In a world of ever more complicated technologies, the winter harvest is refreshingly uncomplicated because all three of these components are well known to most vegetable growers.

What is not well known is the synergy created when they are used in combination, and that is what we continue to explore on a daily basis on our farm.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

With the right strategies and practices, composting on a small farm is surprisingly easy and inexpensive. Just follow these steps for making compost, and your farm will be thriving in no time! The following excerpt is from The Lean Farm Guide to Growing Vegetables by Ben Hartman. It has been adapted for the web. (All photographs by Ben…

Read MoreGarlic mustard: while known as “invasive,” this plant can be consumed in its entirety and has great nutritional value. Plus, the garlic-flavor is a perfect addition to any recipe that calls for mustard! The following are excerpts from Beyond the War on Invasive Species by Tao Orion and The Wild Wisdom of Weeds by Katrina…

Read MoreEveryone loves a refreshing, fermented, nutritious drink…even your garden! Take your fermentation skills out of the kitchen and into the garden by brewing fermented plant juice. The following is an excerpt from The Regenerative Grower’s Guide to Garden Amendments by Nigel Palmer. It has been adapted for the web. How to Make Fermented Plant Juice Fermented…

Read MoreWant to see your crops thrive this upcoming growing season? The key is in soil fertility and health. Spend time maintaining your soil’s health to guarantee bigger and better crops come harvest time! The following is an excerpt from No-Till Intensive Vegetable Culture by Bryan O’Hara. It has been adapted for the web. What Is Soil Fertility?…

Read MoreMany know the effects of catnip on our feline friends, but few realize that catnip has medicinal effects for humans. From stomach aches to reducing fevers, catnip is a versatile herb with many benefits. The next time you grow this plant for your cat you may end up taking a few cuttings for yourself! The…

Read More